'Persona' Takes Jungian Psychology and Runs With It

Though, according to Dr. Matthew Fike, the accuracy is hit or miss.

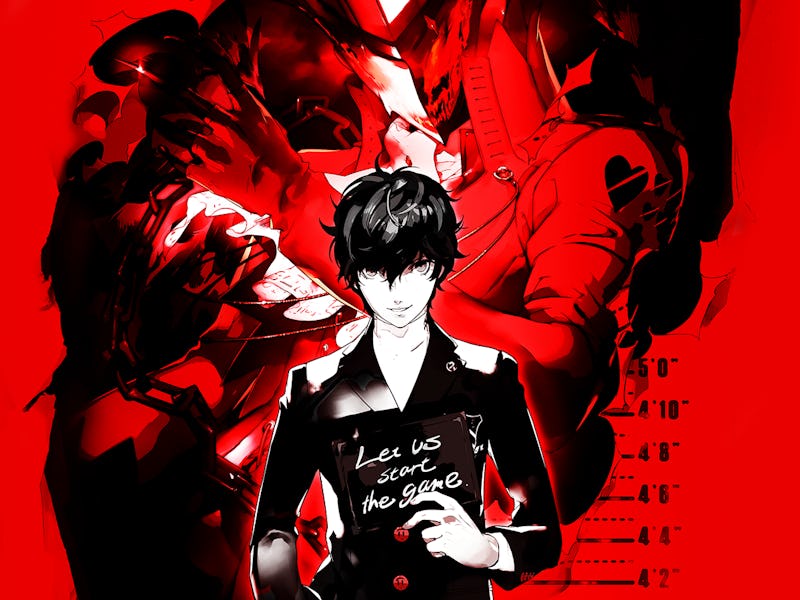

Atlus’s Persona series is very open about its influences from Jungian psychology, like its use of the terminology and visual representations of its concepts. But how close does it hew, exactly? With the highly anticipated release of Persona 5 coming Valentine’s Day next year, Inverse spoke with an expert to see just how well Carl Jung’s works were being adapted.

Dr. Matthew Fike is a teacher of English at Winthrop University where he specializes in classics like Shakespeare and Milton. But what sets him apart from most strict English professors is his interest in psychology as a lens to critique the world around him. Over the course of his career, Dr. Fike has become a Jungian psychology expert with numerous publications under his belt. In his book The One Mind, for example, he discusses the future of literary criticism by applying Jung’s writings on the metaphysical, the paranormal, and the quantum to literature.

'Persona 4' asks the hard questions.

But let’s start with the basics. Carl Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist who invented analytical psychology. This type of psychology, also dubbed Jungian psychology, is what Persona is based on. Its a form of psychotherapy that focuses on the importance of the individual psyche and the pursuit of wholeness. To put that in layman’s terms, people must learn themselves completely, inside and out, and try to become their true, fulfilled self.

The term “persona” is derived from the Latin word, “personae”, which means “mask.” In Jungian psychology, the persona is the mask or masks we wear to assume an identity based on how we feel we should react in certain social situations. Think of the people who are typically calm and keep to themselves, but at parties they open up and get wild, which … doesn’t really translate to the Persona games very well.

This was the first bit of analysis Fike examined, and he was very critical of the usage of Personas as they appeared in battle. The protagonists in the games are all characters who have masks they wear to endure reality, sure, but their demon-like “Personas” awaken when they confront their shadow selves and that doesn’t quite jive with Jung. Personas exist all the time and require no actions to obtain.

“The persona is in the way,” says Fike, “so there’s no delving deeper into it to become stronger. There is a sort of primordial strength that is layered over and the persona has to get out of the way. Also, it’s important to remember that the stronger the persona, the stronger the shadow.”

Shadows are the parts of ourselves that we deny or refuse to acknowledge. They exist as an opposite to our persona and represent everything that pulls us away from what we believe is our ideal self. For example, in Persona 4, Kanji refuses to accept that he has feminine interests, because it goes against his view of masculinity. Not surprisingly, his shadow manifests itself as an overly feminine male who embraces overtly counter-sexual mannerisms.

Dr. Fike agreed with how this was handled in the games since it went along with Jung’s belief that it’s only when we accept our shadows, our insecurities, and our darkest thoughts that we get closer to achieving wholeness. But when I mentioned the idea of a blank-slate main character with no shadow, he seemed equally alarmed and intrigued, stating bluntly, “Everyone has a shadow.”

Despite this, both P3 and P4 protagonists, Makoto and Yu, have no shadows, which seems to point to the fact that they have made peace with their own faults and darkness. This is a benefit to them, since it allows them to help others get to the same place that they have by helping them accept their own shadows. It also helps them become a vehicle for the will of the players.

In the series, a feature called “Social Links” exists to help grow characters and their ability to cope with their own shadows. As the players control the characters, they are able to make social choices and utilize their own personas outside of the game in order to grow both their character and the characters that they interact with in game. These “Social Links” are also tied to tarot cards which, as Fike points out, are quite similar to the archetypal figures that Jung outlined in his studies.

“You’re playing at individuation through the agency and inspiration of the characters,” says Fike, “and it could lead people closer to achieving wholeness in reality if they were to attempt the same feats in their own lives. But it could also have the opposite effect if they only do it in the video game.”

Another point for accuracy was the incorporation of the collective unconscious and the personal unconscious. According to Jung, there are things that are shared between all beings of the same species, and then there are things that exist within us based on our individual feelings, thoughts, and perceptions. In P3, the collective unconscious is represented as Tartarus and the Dark Hour, and in P4 it is the TV World/ Midnight Channel.

However, the personal unconscious takes form here as well when we venture into the realms that are created by individuals’ shadows. Returning to P4’s Kanji, his personal unconscious manifests itself to go against his ideas of masculinity as a counter-sexual bath house where his shadow flaunts his femininity. His complex about being seen as homosexual has created his shadow and shaped his own personal unconscious without him realizing it.

Lastly, and probably the most interesting feature, is the personas themselves being presented as monsters of a sort. In most Jungian corners, it doesn’t make sense outside of a visual flavor for the games, but there is a slight connection. For a long time, Carl Jung’s family hid what is known as his Red Book from the world because it made him look insane. In it, he had written about struggles with demons and drawn many pictures of monsters. This could be a neat bit of inspiration for Atlus, but stylistic flavoring to match Japanese lore is more probable considering the medium.

Persona as a series dares to use deep psychology to create an interactive narrative that the two of us could have talked about for days, and Fike was confident that Jung would feel the same way.

“I think Jung would be quite interested in a game based on his works since video games come from imagination,” Fike says, “but he would be wary that they could promote antisocial behaviors instead of inspiring the players toward their own individuation.”

In other words, Jung would likely find it both fascinating and foreboding. Persona 5 is scheduled to release on February 14, 2017 for PlayStation 3 and PlayStation 4.