How a 2,000-Year-Old Shipwrecked Skeleton Survived

This Roman-era cargo ship is ancient tragedy, modern scientific bounty.

In 65 BC, a ship wrecked and sank off the Greek Island of Antikythera. One victim’s perfectly preserved skeleton may hold untold secrets to the world he inhabited.

But how did a waterlogged skeleton discovered during a dive last month fend off decomposition for two millennia, with bones that still retain fragments of DNA? After all, bodies lost at sea are usually swept away by currents, pulled apart by predators, and decomposed with the help of microbes and corrosive salt water.

Here’s the thing: For a fighting chance to survive into the future, a corpse must become buried in sediment very quickly. The skeleton doesn’t quite count as a fossil — typically defined as organic matter or traces of it preserved for about 10,000 years — but it was well on its way. In this case, the victim was inside the ship when it wrecked. The seafloor muck stirred up by the ship’s tumble to the bottom must have settled in the hull, covering people and goods trapped within.

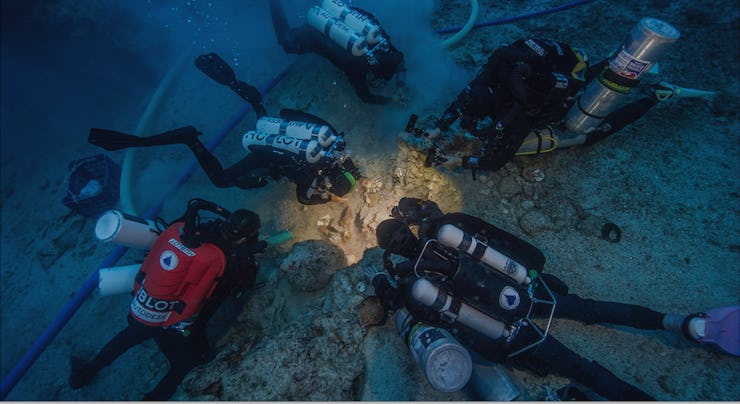

Underwater excavation is a tedious process. It’s similar to archeological digs on ground, in that layers of sediment are slowly and methodically peeled away to reveal the contents within. A hose sucks up sand and sediment to keep it from clouding the water, and it’s pretty tough to go so deep underwater to tediously search for artifacts for long periods of time.

With Antikythera, scuba divers unearthed parts of the sailor’s arms, legs, and skull, including a hard piece of bone behind each ear that researchers think is their best shot at extracting intact DNA. The scientists are waiting on permission from the Greek government to remove samples for analysis. If successful, we might one day know the victim’s ancestry. Maybe, just maybe, we might even learn what his face could have looked like.